The Quarantine Came in March 2021

And before long, friends who’d visited their kitchens to brew coffee and microwave leftovers were baking up a storm. It was a harmless enough substitute for normal life, even though it was practiced somewhat abnormally. Like a rookie golfer who buys a set of Callaways to overcome a left hook, a neophyte’s first step was to acquire unnecessary but expensive equipment. How about a $179.95 quart container that fits inside a heated dome to cosset your starter, or a $59 lame to score the top of your loaf when a sharp knife would do? Kitchens outfitted, friends who couldn’t boil an egg were leaving loaves of bread on my doorstep. A trend had begun.

I wrote thank you notes to all, although not to encourage them. By then I had excess inventory of my own to dispose of. Not to boast, but baking was the business my family was in and the loaves on my doorstep reminded me of the doorstops I used to produce. By the time of COVID, mine were crisp and crackly outside, lacy and chewy inside.

As well they should be. I’d been making bread under the white thumb of my mother since I was six. Not that she was a domestic goddess. A master bridge player who could count cards like a croupier and taught nursery school by day, she only spent enough time in the kitchen to keep us alive. It wasn’t until my older brother Jimmy was born with brain damage that meant he would be home-schooled, did she stay home. By about six, his happy place was on a stool in the kitchen where he pronounced he was there to help.

That changed everything. My mother had all the help she needed from Bird’s Eye, and no interest in challenging its expertise. But she had to up her home game to keep Jimmy occupied. She gradually found her happy place specializing in bread because no one else she knew was doing that. Two cups of Pillsbury flour, one cup of water, a packet of yeast and a pinch of salt that transformed into a fluffy loaf by dinner time? So much more gratifying than wrestling a turkey to the table on Thanksgiving. Soon, with her sous-chef, my mother was producing loaves like Martha Stewart on steroids. We couldn’t eat it all and while we didn’t call it brunch, on Sundays she soaked bread that had gone stale in milky eggs, fried several pounds of bacon, and invited everyone she ran into at Mass over. Word got out among our Protestant neighbors who discovered a pressing need to borrow a cup of sugar about the time 11 o’clock mass at Good Shepherd let out. If Washington had someone like my mother, Democrats might not like the Republican tariffs, but they would still all get along.

When the kitchen wasn't occupied with baking, it was piled with the fruits of a garden my brother loved, often gone weedy, but nonetheless producing tomato plants twice his height and zucchinis the size of his head. Every summer there was a forced march to boil Mason jars and preserve the bounty in, of course, an industrial size deep freezer my father had built a covered porch to contain.

All those people dropping in, constant activity, no privacy, I’d head to my room to read the latest Nancy Drew until peace was restored. It rarely was and I gradually succumbed. I liked when my parents were happy, and they were when my brother was. Restless, my mother looked for a challenge: she’d already gone rogue with pretzels and cinnamon rolls, cheese sticks and crackers. She’d heard of a mysterious dough that rose on its own, known on the coasts as sourdough, but not at all in our suburb of Harrisburg, Pa. I went to the library and the “Book of Bread” by Amelia Simmons was out of print. The otherwise encyclopedic “Joy of Cooking” (that we didn’t own; my mother relied solely on a battered Better Homes & Garden cookbook that came free with a magazine subscription) had only one off-putting paragraph on the subject. Accompanied by a warning as urgent as the Surgeon General’s, it counseled that sourdough “should be attempted only by the adventurous, persistent, and leisurely.”

Get out the hazmat suits. My mother met all the requirements save “leisurely” and went to work. She set up four Mason jars borrowed from her canning operation, filled them with equal amounts of flour and water, and fed them daily, discarding the top layer as directed, although grudgingly, since we were survivalists who wasted nothing. Before school, I raced downstairs to see how far the starter had risen as if it were Christmas morning. After ten days, the bubbling mass had risen as high as the word “Mason,” and without an assist from a $180 heated dome. Lift off!

But what was this “slap and fold” business? Like the reporter I wanted to be, I called the Boudin Bakery in San Francisco, famed for a starter gurgling since 1849, late at night when the rates were low. Lift two sides of the dough with your floured fingers until it almost tears, then slap it down and over to the other side as hard as possible to release the gasses. Repeat and repeat and repeat at fifteen minute to half hour intervals for an eternity. After it ferments for 12 hours, turn it out onto a floured surface to let it rest, and be sure to give yourself one, because you still have miles to go.

I tried to speed-slap my way to a better mousetrap. I mashed together the no-frills approach of the King Arthur Flour website, with the exuberant tutorials of Joshua Weissman, and the efficient guidance of Lisa, trading under the banner, Farmhouse on Boone, who timed her 12-hour ferment until her brood of eight, and she, were down for the night

No matter, sourdough eats your days and takes prisoners. My dough would become the consistency of Elmer’s glue, runny at first but so dry later it would take a Swiss Army knife to scrape it off my hands. I’d add a little flour to the glue to thicken it. Then, the dough too dry, I’d add some water. Rinse and repeat. Therein lies madness.

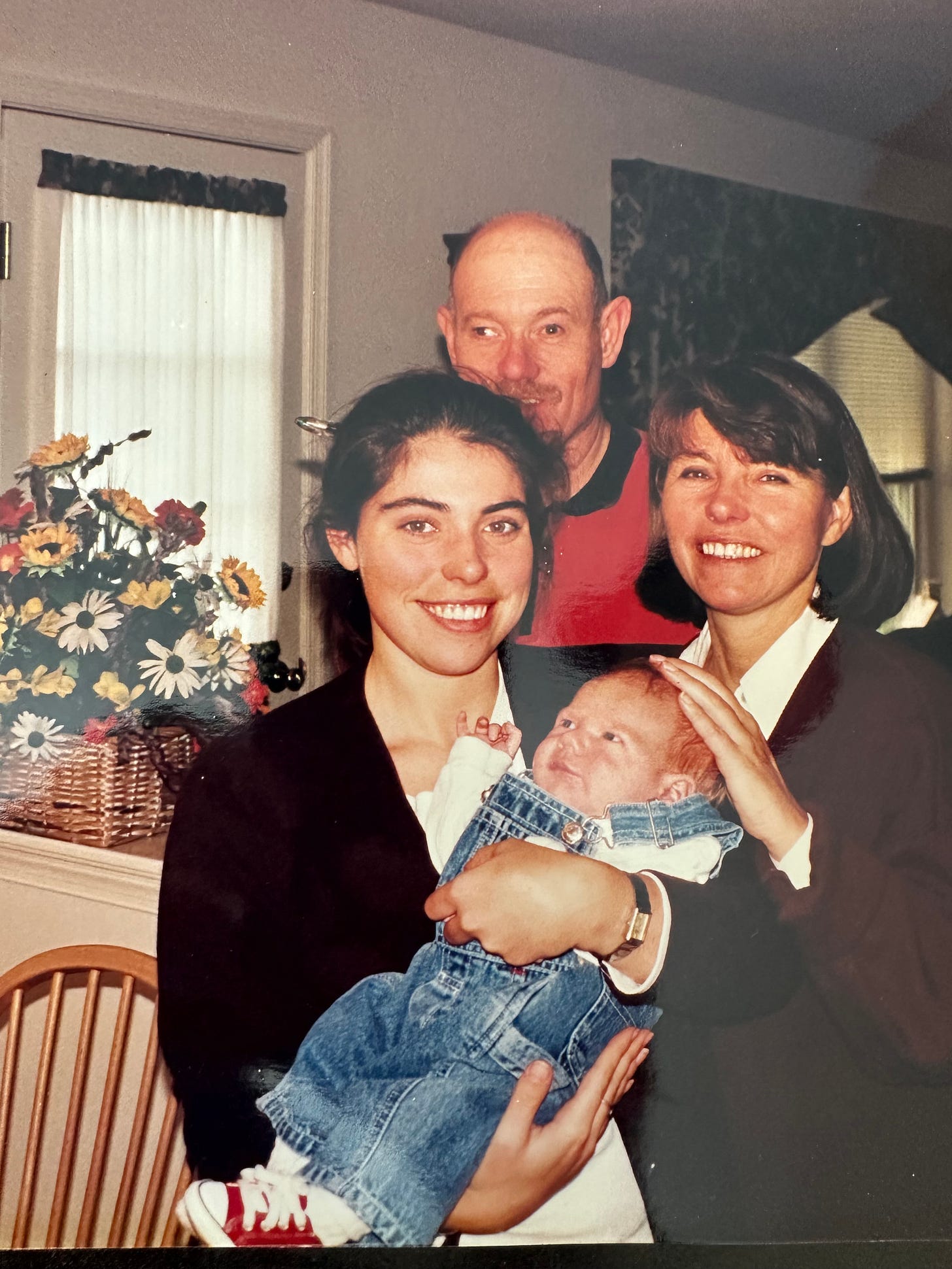

By the time my mother taught my daughter to bake, she had returned to Pillsbury. The hard truth of sourdough is that like a child or a pet, it requires that you to be there for it. There are no shortcuts when leavain is part of the conversation. I asked myself if I could live a normal life having to humor my starter, measure ingredients to the microgram, deal with the water-flour dilemma, and wait an hour while the oven preheated to a temperature that could smelt iron? There had to be another way to have my bread and eat it too.

There is and thy name is Fleishmann’s. Could it be that Mother Knew Best? Never, you purists of the quarantine cry! Yeast is the devil’s work. No, the devil’s work is a recipe posted only in grams. Is it a crime to put candles on a birthday cake made from a box of Betty Crocker’s Chocolate Fudge mix if otherwise there'd be no cake? At worst, it’s a misdemeanor, unless someone gets sick from the xanthan gum. Likewise, no one is injured in the making of bread that takes hours less fussing, a packet of yeast, and can acquire a bit of the tang reminiscent of its labor intensive sibling with a splash of vinegar (it‘s not a Schedule A drug; go on, add a few drops).

Then in 2006 came the bread moonshot that changed everything. The New York Times, which publishes more cooking news than any other kind, printed the recipe of Jim Lahey, owner of the Sullivan Street Bakery on Ninth Avenue, for No-Knead bread. Where’s the fun in that, you ask? I found it in getting to smell the roses and having eight hours of sleep at night. Here’s what to do: Mix 1/4 teaspoon of yeast, 2 teaspoons of salt, and three cups of flour in 1 ⅓ cups of water and then go to bed. The rest of the story, for those who believe the perfect is the enemy of the good, is here.

Here is one of the most popular recipes The Times has ever published, courtesy of Jim Lahey, owner of Sullivan Street Bakery It requires no kneading. It uses no special ingredients, equipment or techniques.

The recipe was amended over the years and the amount of flour increased to 3 ½ cups specifically to help me solve my flour-water problem and retire my Swiss Army knife. Now the only thing No-Knead bread needs is a PR pro experienced in name changes, like Facebook to Meta. A suggestion: It isn’t really no-knead. While you sleep, the dough kneads itself!

I didn’t grow up fast enough and my parents didn’t live long enough for me to thank them. Much of what they heard were complaints about being stuck at home while my schoolmates roamed cage-free. My household didn't look like the sedate ones of my friends whose fathers were lawyers and bankers. I didn’t see that I had those friends because we weren’t like that–the energy and the messes, friends up to their elbows in flour making pizza with all the toppings that would fit, although we drew the line at pineapple, nothing you match at a country club.

After my parents died, Jimmy came to live with me. I moved out of my Georgetown house, with stairs so narrow he was bound to fall, to an apartment. It was a kinder, gentler time in Washington, where no one, much less a president, would mock someone different, and it was an easier transition than I imagined. The kindness of strangers is remarkable and he was remarkably likable. Tenants stood up, and in, for the old neighborhood. We made bread on the weekends and ice cream at night in the Donvier he could churn, not the boring automatic Cuisinart he couldn’t. At the Safeway, he'd slip something off-list into the grocery cart, counting on me to be shocked at checkout. Our only flashpoint was the TV. I wanted to watch the PBS NewsHour. He wanted "Columbo." And so it was I learned to love Peter Falk.

Jimmy didn't like going out much but like my schoolmates, my friends didn’t mind coming over to ingest a significant portion of their Required Daily Intake of nutrients. He would never be lonely as long as there were doormen with a lot of time on their hands. One morning, in a pinch, I took him to a newsmaker breakfast dressed in his spiffy suit from my wedding. We found a table in the crowded dining room and the reporter on his left I didn't know made polite conversation. "Who are you with?" he asked. "My sister," he replied. I was talking to a friend on my right and couldn’t jump in to pre-empt the inevitable follow-up. "Who's your sister with?" Jimmy said blithely, "She's with me."

And so he was. I could barely remember when I wanted to hide in my room with "The Secret of the Old Clock" when a few steps away life, including my younger brother, was galloping on. What Jimmy knew of Washington were trips where my father would drive us around ogling the monuments and museums without venturing inside because paying to park was waste, fraud, and abuse of hard-earned money. When they came to stay with me after the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster, after two weeks they so longed for their formica kitchen over my sterile stainless steel one, they went home, even though it meant inhaling radioactive gas.

By the time Jimmy arrived, my house wasn’t so different from the one he grew up in. We spent most of our time in the kitchen, with a TV and the same mismatched blue and white china, Mason jars, bread pans, and routine he knew so well. He couldn’t drive a car but he loved washing them and he had a thriving business–he knew the difference between five, ten, and twenty dollar bills–in the parking lot. He loved to eat. I loved to cook. It’s amazing the connection that combination can forge.

I fantasized my parents were at his memorial service. They would have been comfortable with our neighbors who were as kind as theirs--my friends who had become his, the doormen and the staff who kept the building running, the tenants who Jimmy knew better than I did, his doctors, a priest, and his social worker. I dreaded the responsibility of Jimmy coming to live with me. I was devastated when he was gone.